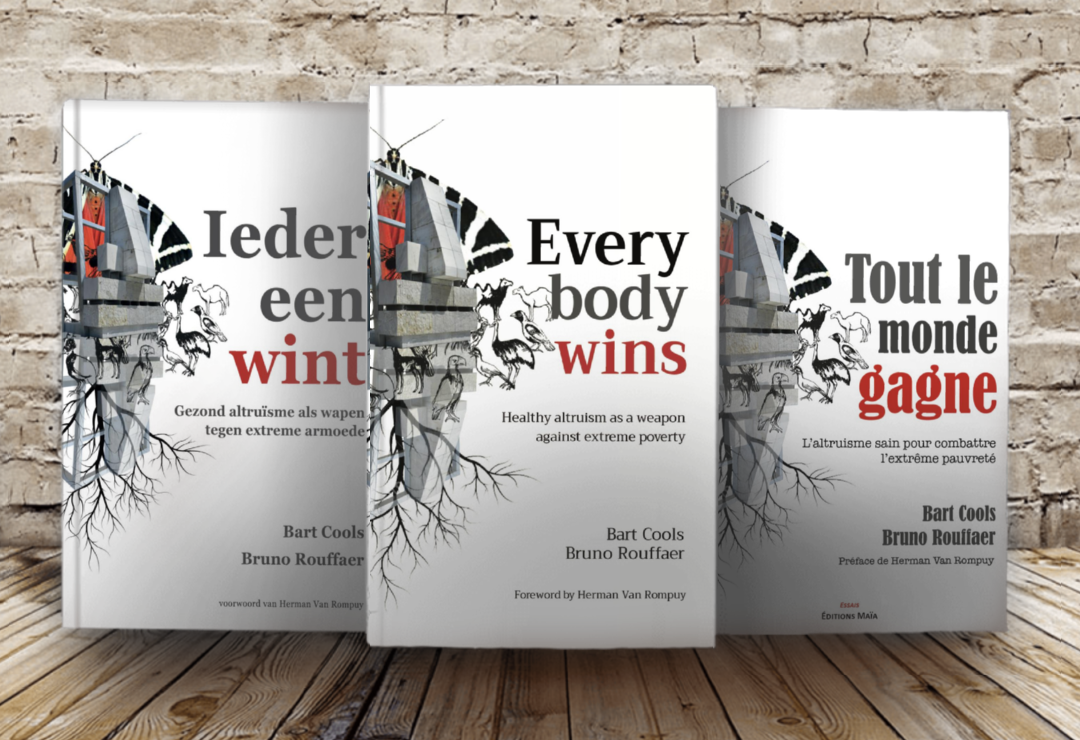

(Extract from the book “Everybody wins”, by Bart Cools and Bruno Rouffaer)

Through the lens of someone living in a “rich” country, the perception of life for people living in extreme poverty is usually distorted. Low-income countries are much more developed than most people think. And far fewer people live there than most of us think. Conversely, some high-income countries are much less developed than we think. And many more people live in poverty in those countries than we think. Our view of poverty depends a lot on who we are, our generation, our profession, and where we live and have lived on Dollar Street.

Money is not the only meaningful measure of poverty. Indeed, large portions of the population, including the poorest, live outside the “money economy”. If we take the quality of life into account, some of the reality may look different. To understand the world properly, we need different perspectives. Depending on which measure we use, a country’s place in the world rankings may vary. For example, European countries score lower on the Positive Experience Index than Central American countries, even though average income levels are significantly higher in Europe.

Issues of poverty intersect with other issues, such as human rights, gender, environment, climate change, conflict, or urban-rural disparities. Focusing on a single component is easier to take action, but will only address part of the problem.

In 2017, 3.9% of children under 5 died. That’s bad. In 1800, almost half of children under 5 died (44%). So we are doing much better after all. In 2015, 14% of the world’s adults could neither read nor write. That’s too many! In 1960, that figure was 58%. Does it still sound so bad now? It is important to distinguish between a level (for example: bad) and an evolution (for example: better). Things can be both better and bad.

Step by step, extreme poverty in the world is declining. Not on every dimension every year, but as a trend. Although the situation is not rosy and the world still faces enormous challenges, we have made immense progress. Since 1990, over 1 billion people have escaped extreme poverty and infant mortality has fallen by more than half. That is an amazing achievement. But there are still about 700 million people on this planet who struggle to meet their basic needs every day. And more than 6,000 children still die every day from infectious diseases that are perfectly avoidable or treatable. That’s bad.

Think of the world as a premature baby in an incubator: Does it make sense to say that the baby’s situation is improving? Yes, absolutely. Does it make sense to say that the situation is bad? Yes, absolutely. Does “things are improving” mean that everything is fine and that we should all relax and not worry anymore? No, not at all. Do we have to choose between bad and yet better? Certainly not. It’s both. It’s both bad and better. Better, and bad, at the same time. This is how we should think about world poverty. Better. So our efforts make a difference and there is reason to be hopeful and persistent. Bad – there’s no time to lose, so let’s not be complacent, poverty remains one of the world’s greatest challenges.

Extreme poverty is declining year after year. That’s a fact. Extreme poverty will be eradicated by 2030. That is a myth. Conflict, poor governance, slow economic growth, and a lack of social measures for the weakest keep some populations in a stranglehold and make it difficult to escape. The global pandemic makes this precarious process even more challenging.

Imagine a ladder where the lowest rungs of the ladder represent the countries with the lowest and the highest rungs the countries with the highest per capita income. Climbing this economic development ladder means the end of hunger and misery and generally leads to healthier, happier, and longer-lived people. This is the concept described by Jeffrey Sachs in “The End of Poverty.”

People living in extreme poverty could not set foot on this ladder, and cannot do so on their own. All their efforts are focused on survival. They do not yet have the economic base necessary for further development. They are too poor to save for education, health care, or investment in basic services.

These people need help to get a foot on the first rung of the development ladder. They need basic infrastructure to meet their needs for food and clean water. They need help to acquire education and develop expertise and skills. Only then will they have a real chance of moving forward and being able to offer their children hope for a better future.

More information on the book “Everybody wins”: www.everybody-wins.eu